UBC home to unique blood-donation clinic for those banned elsewhere

NetCAD offers those who are ineligible a chance to give blood — not for transfusion, but for research

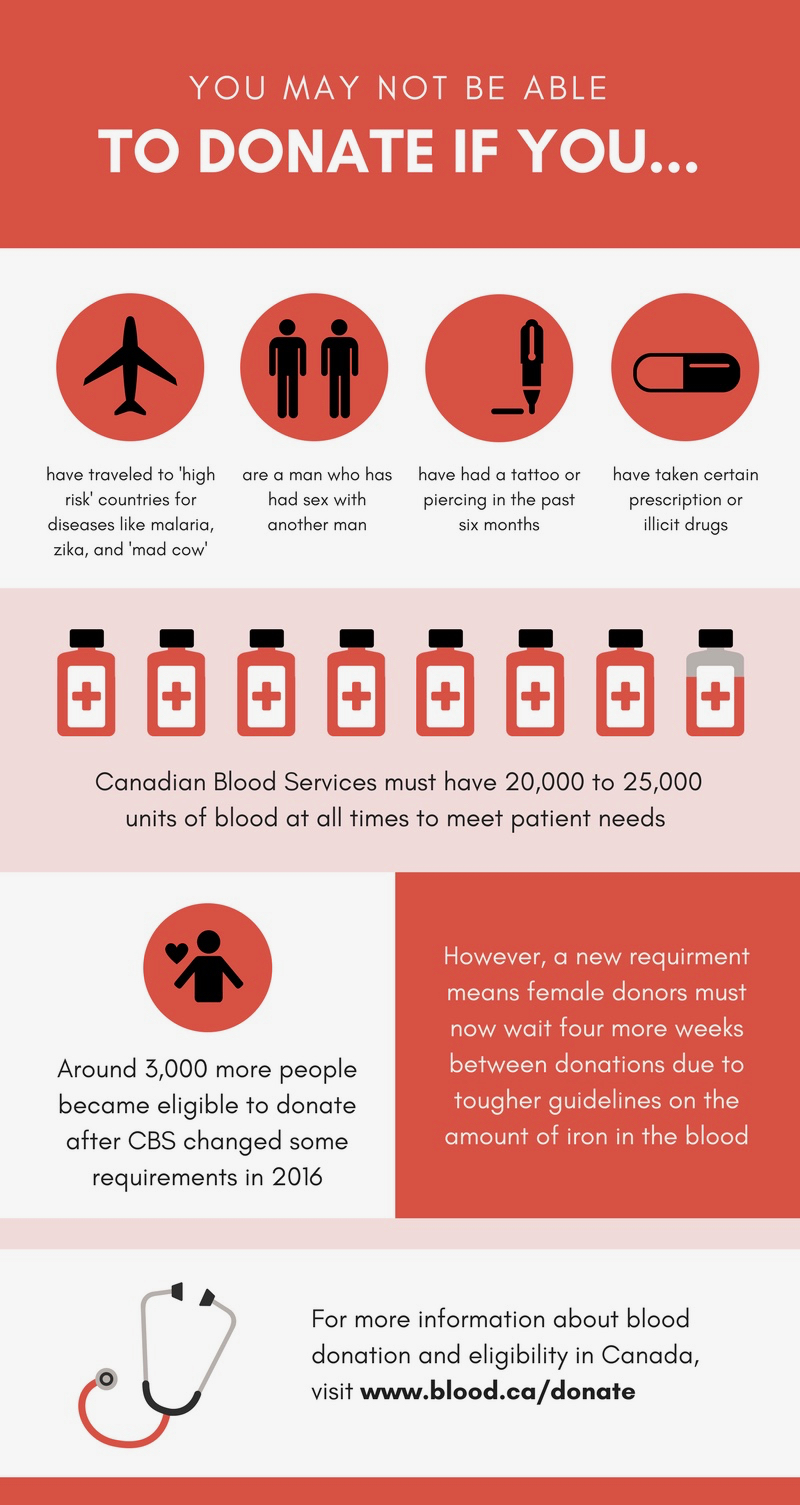

Half of all Canadians are ineligible to give blood.

But NetCAD, a unique blood–donation clinic on the University of British Columbia’s campus, offers those who are ineligible a chance to give — not for transfusion, but for research.

Canadian Blood Services created netCAD Blood for Research facility in 2003 in order to support innovation aimed at strengthening Canada’s blood system. It supplies blood to research projects in nine cities across the country.

NetCAD allows donors who are deferred and excluded the chance to support projects that seek to end the need for some exclusions altogether.

“It’s is a unique facility among blood operators around the world,” said Jenny Ryan, a CBS communications specialist. She likened netCAD to a “‘sandbox,’ where new technologies are tested with the goal of improving blood manufacturing and patient care.”

Despite this one-of-a-kind opportunity, public awareness of netCAD is low.

“We have limited resources to advertise netCAD, although we have partnered in the past with local organizations to promote donation,” Ryan said. “Having more deferred donors attend our netCAD clinic would greatly help in meeting the research community needs.”

Balancing safety and patient need

CBS is responsible for providing safe blood products to Canadians. It has strict regulations about who can donate and when. CBS must collect 17,000 units of blood each week to meet patient needs, so when donations are slow, Canada’s blood supply fluctuates and periodically dips into critical shortages.

[toggle title=”Are you eligible to donate blood? “]

[/toggle]

NetCAD’s research is tackling some of these persistent challenges.

“There is a constant need for donors because blood doesn’t last very long on the shelf,” said Ryan. Platelets last just five days, while red blood cells may be stored for up to 42 days.

NetCAD is currently using microbiology to test how to improve the clotting ability and longevity of platelets.

Blood’s short lifespan, coupled with a large number of Canadians who are either ineligible or choose not to donate, fosters recurring shortages. Only one in 60 eligible donors, or around two per cent of all Canadians, will give blood.

It’s in who to give?

Despite the need for more donors, many Canadians are regularly turned away from CBS clinics.

For instance, men who have sex with men remain barred from donating unless they have been abstinent for at least one year, due to perceived concerns about the transmission of HIV. A lifetime ban was lifted in 2013 and, in 2016, the deferral period was lowered to one year from five.

Advocacy groups including the Health Initiative for Men and members of the scientific community have criticized the deferral period as stigmatizing.

CBS maintains that the deferral for men who have sex with men is based on science and a lack of sufficient research, not stigma.

“Most public–health research has focused on men who have sex with men with behaviours that put them at high risk of infectious disease,” the CBS website reads.“There is little data available for those with low risk, such as those in long-term monogamous relationships. New research must be done … for low-risk groups to be included as eligible donors without introducing more risk to blood safety.”

Blood collected at netCAD supplies several projects focused on studying and fighting HIV.

One project based in Winnipeg, Man., is studying how HIV spreads in the body by looking at white-blood-cell responses to the virus in mice. Researchers hope to better understand targeted mechanisms to suppress HIV replication.

Another project out of London, Ont., is studying the potential of antiviral immune responses and protein production as a means to develop HIV vaccines and cures.

These projects mean that donors who are currently subject to deferrals and exclusions might be able to donate for transfusion in the future.

“The impact donors at netCAD have on the future of the blood system and on patient care cannot be overstated,” said Janet McManus, the manager at netCAD. “With more donors, we believe we could double the number of research projects supported.”