Future growing dim for Vancouver tanning salons

Business-licence records in Vancouver show over the past 22 years the number of tanning salons in the city has been cut in half

Many Vancouver tanning salons are admitting defeat and turning off their lights as cancer-wary consumers heed calls to stay away.

Brent McGuire, an Ontario native and former tanning-bed user says tanning has helped him combat Vancouver’s dismal climate over the past year, but the scary side effects are making him rethink whether tanning is worth it.

“I think science is showing that tanning is right up there with smoking, there’s not really a safe or healthy way to do it,” says McGuire.

Business-licence records from the city of Vancouver open data catalog show that, over the past 22 years, the number of tanning salons in the city has been cut in half from 30 to 16. The biggest drop has come in the last two years from 2014 to 2016, where eight tanning salons went out of business.

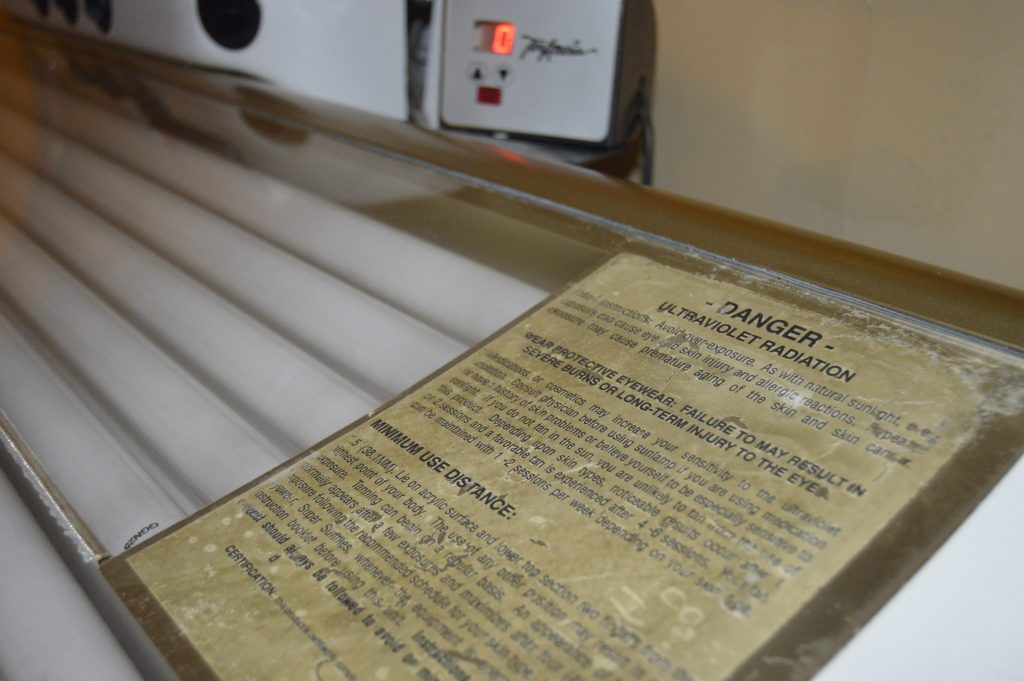

The dimming of tanning lights can’t come fast enough for medical professionals who have been trying to educate people for years on the harmful effects that tanning beds have on our skin. Research shows that tanning can increase the risk of skin cancer.

The government introduces legislation to regulate the sun tanning industry

The biggest hit to the tanning industry came in 2012 when the B.C. government approved legislation that banned minors under the age of 18 from tanning salons. The desperate plea from researchers and doctors asking the government to take a stand on this issue is now making waves in the city of Vancouver.

Vancouver salon owners were hesitant to discuss the state of the industry.

However, Steven Gilroy, executive director of the Joint Canadian Tanning Association, says many reasons explain the decline in salons.

“Most of what was depleted (closed) was old salons that hadn’t upgraded equipment,” said Gilroy.

“What eliminates the risk [of tanning] is having industry-certified trained operators who are aware of people’s skin types and know how to safely operate the equipment.”

Sunil Kalia, an assistant professor at the Photomedicine Institute and at Vancouver Coastal Health, is ecstatic to see the drop because he believes the decline of tanning salons is closely correlated to the efforts of the provincial government.

Kalia is looking to educate one group of people on the risks of tanning

Following the success of the ban on minors, Kalia and the Canadian Cancer Society are gearing up to launch a campaign in early spring with the goal of informing youth on the hazards of suntanning. With targeted messages and ultra-violet cameras, which are able to show the acute sun damage, Kalia hopes high-school students will understand the risks they’re assuming if they tan.

“Different messages relay to people differently” Kalia said, “and it’s hard for someone at a younger age for them to conceptualize that they’re at an increased risk for skin cancer, because the effects of UV exposure don’t usually show up until later.”

Following an initial campaign that took place last year, Kalia says some changes are going to be made.

“[Tanning is most popular] prior to going to sunny destinations in the winter and right before the summer months. We want to target these campaigns to reduce the use of tanning beds during these peak times.”

“I enjoy tanning,” McGuire,who admits that “it’s a hard habit to break because it made me feel better in the winters. It’s tough because not everyone listens, just because people tell you to eat better or exercise more, doesn’t mean you’re going to do it. I think with tanning it’s sort of the same thing”

Researchers are still struggling to enforce their message

Some of the biggest challenges that Kalia says researchers and doctors are facing is the lack of ability to remind people throughout the year. He says the information his team received from a survey done after last year’s campaign reported that youth are more influenced by physicians than they are their peers. But they don’t always see a doctor regularly.

“You can do these campaigns that will influence people to change their behaviour for short periods of time, but the challenge is that people forget,” Kalia says. “Not everyone that is at risk for skin cancer is seeing a physician and that’s why these campaigns are fundamental.”

For this reason, Kalia thinks it’s important for governments to work with organizations like the Canadian Cancer Society to implement regulations that protect people and reinforce the messages that these groups advocate.