Why a tiny chunk of U.S. land attached to Canada, now cut off by coronavirus, has always been isolated

Vancouver’s slice of America is now locked down and cut off from the U.S. mainland. Why does it exist in the first place?

Border friction and isolation were part of life in Point Roberts long before the coronavirus made itself known. Now the tiny American town is dealing with the full effects of these amid the global pandemic — locked down and cut off from the rest of its country.

How did this particular place come to exist in the first place? The Thunderbird has the history.

First, where is Point Roberts?

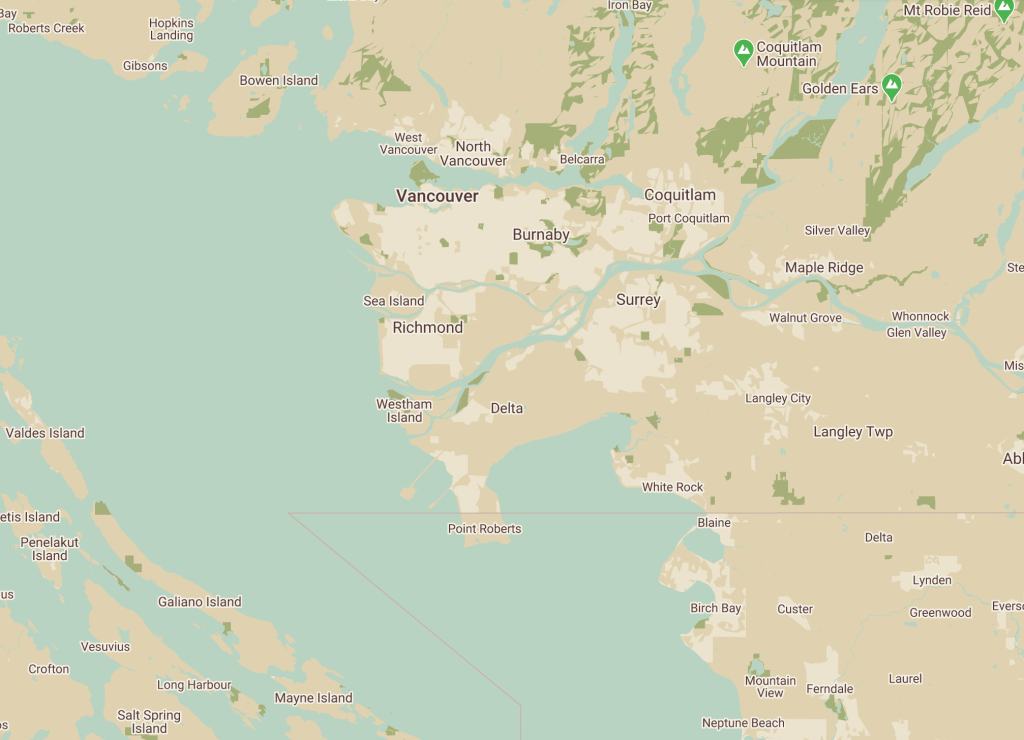

Open a map of B.C.’s Lower Mainland and find downtown Vancouver. Easy enough. Now trace your finger downward along Cambie Street, past Oakridge and south Vancouver and into Richmond. Continue south across the Fraser River into Delta, and even further down into Tsawwassen. Great. Keep going, but don’t touch the water. You’ll find you’ve come to a dead end.

You’ve arrived.

What is Point Roberts?

It’s a tiny piece of the United States, stuck to Canada.

Point Roberts is a 13-square-kilometre American exclave about 40 minutes south of Vancouver: a fragment of the U.S. separated from the rest of the country by water and foreign territory — Canada, in this case.

The point was the only place Stephen Falk knew about “out west” when he moved from Philadelphia to the point seven years ago to join his brother who’d been spending the summers here.

“It’s probably the closest you can get to Vancouver without being in Canada,” Falk says, who serves on four district boards and committees, and considers himself enmeshed in the community.

The border between Point Roberts and Canada is a far cry from the walls the nation’s president boasts about. It’s mostly a drainage ditch running next to hedges and the odd waist-high concrete barrier. It’s easy to miss.

For those who have business to conduct on the U.S. mainland, the border can be a hassle. Lineups are common on either side of the crossing. There’s no hospital, no doctor, and no dentist in Point Roberts. There is the Point Roberts Primary School, but it only goes up to Grade 3. Beyond that, schoolkids cross the border four times a day, to Blaine and back, by bus to attend class. There are around 180 people under the age of 18 in the point.

How did Point Roberts come to be?

It was an accident.

B.C. writer Douglas Coupland wrote that “if you were from outer space and we’re shown a topographic map of North America and then told to come up with the stupidest way possible to slice it up, you’d probably say, ‘Let’s put a straight line right across the middle.’”

For better or worse, that’s the way things happened.

In 1846, the British and the Americans signed the Oregon Treaty, dividing the Pacific Northwest along the 49th parallel to the Strait of Georgia. Neither side realized the agreement would cut off the southernmost 3.2 kilometres from what has since become greater Vancouver.

“The border being set at the 49th parallel happened to cut off this five-square-mile chunk of land that otherwise, by all rights, should really be Canadian,” says Falk.

Surveyors noticed the problem in 1856, prompting the British to try to find a way to keep Point Roberts in Canada in exchange for another piece of territory. But in 1859, on nearby San Juan Island, settled by both British and Americans, a large black pig belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company wandered onto American Lyman A. Cutler’s farm and began rooting his garden. Cutler shot and killed the pig, marking the beginning of the Pig War. (The only casualty was the pig.)

Troops were sent by both countries, and, in an effort to assert American interests in the region, the U.S. president designated Point Roberts a military reservation. The possibility of a border deal evaporated.

Eventually tensions settled and the two sides agreed to arbitration by the German kaiser, who sided with the U.S. The border along the 49th parallel stayed put, and the point stayed American.

With the stroke of a pen and the death of a pig, Point Roberts was born.

The American military eventually abandoned the point, leaving it to squatters, most of whom were Icelanders attracted by the fishing and farming in the area.

Who’s there?

Point Roberts is a 1,200-person community.

Many who live here are descendants of the Icelandic squatters of the past. There are also Icelandic horses in the point.

Many year-round residents are elderly or retired, although some younger folks have found ways to make a living in Point Roberts, like Abigail Frost, a gardener originally from Georgia.

“We’re all here ‘cause we’re not ‘all there,’” she says, laughing. “You have to kinda get along with your neighbours, because you live at the end of the road.”

There are also many Canadians.

As highway access improved over the years, Canadians began setting up vacation homes in the point — by some estimates, 1,400 of the more than 2,000 homes in Point Roberts are seasonal homes.

As one resident put it, the national boundary is in conflict with ownership: although the territory is technically American, Canadians own most of the property. Some say this means Point Roberts should have never been part of the U.S.

Point Robert’s nationality hasn’t stopped Iolanda and Egidio Trasolini from calling it their second home. The Canadian couple has owned a summer home here since 1969. The Trasolinis drive down every year from Vancouver, where they live. Their children also have a condominium in the point.

Egidio, 89, a former construction worker, built the Point Roberts Marina, which he owned and later sold.

“When we came here there was nothing,” he says, turning to the surrounding properties.

Falk, an American, calls Canadians the “economic lifeblood of Point Roberts.”

He says, “They have no say in what happens, but they tend to be supportive of the things that are going on. It’s not really a conflict, but a feature.”

Most permanent residents are American. Carol Julius was born in Bellingham, Wash., and brought back to Point Roberts, where she was raised. Julius lives in the home her parents built, one of the original houses in Point Roberts, which backs onto a beach at the south end of the point.

“Don’t tell anybody,” she says of Point Roberts, smiling. “We try to keep it a secret.”

Why doesn’t Point Roberts give up on being American and join Canada?

There’s been talk. There’s still talk. But it’s unlikely.

The border is, for the most part, Point Robert’s raison d’être.

Nate Berg, a Los Angeles-based journalist, might have said it best, deploying a somewhat crude simile in a piece for CityLab: “Point Roberts is like the foreskin of America; cutting it off probably would have been more convenient, but keeping it has some benefits.”

Canadians swarm the point year-round, making day trips to fill up on gas, which is about 20 to 30 per cent cheaper than it is north of the border. A 2013/14 survey by Western Washington University’s Border Policy Research Institute found that 40 per cent of the border crossings into Point Roberts were for gas. Prices on the more than 60 gas pumps in the point are labeled in litres, not gallons. Canadians also come for cheap liquor and groceries.

Real estate in the point is considerably cheaper than in Vancouver. Like their American counterparts, Canadian owners pay local property taxes, providing what Falk calls “a good reservoir of funding.”

Point Roberts is also home to a thriving parcel industry. If you’re looking for a reason to stop by for a peek, have your next parcel from the U.S. shipped to at one of the five shipping stores in the point. It’s cheaper to ship domestically.

For now, the border between the U.S. and Canada remains restricted to essential services. Canadians will have to wait for the coronavirus to subside before visiting.

Point Roberts will be here when the world returns to normal, as strange and as welcoming as before.