The Eternal Apprentice

Work is paid. That’s a norm in our society, and an expectation of highly trained professionals. Except in dance. Within…

Work is paid. That’s a norm in our society, and an expectation of highly trained professionals.

Except in dance.

Within the grossly underpaid fine arts, only theatre comes close to the lack of pay for dance. There are so few dance jobs out there that dancers should be grateful to be dancing – and pay? What a bonus!

It’s a funding issue, surely, and most choreographers want to be able to pay their dancers. But they can tiptoe past the tricky issue of wages by taking on an apprentice.

Special grants have been created to support these emerging artists and so project with apprentices gets funded. But the apprentices work for free, often rehearsing and performing alongside paid professionals.

It’s supposed to be a leg-up. It becomes a problem when the jump to getting paid never happens. (Or a jump from inadequate pay – think honorarium, or in-kind pay, or at most a small grant you apply for on your own.)

Your dance career starts to look like a never-ending series of apprenticeships.

I have been an apprentice twice, along with almost all the dancers I know, including a friend who is nearing two years as an apprentice.

What’s that saying…three-times an apprentice, never a dancer?

This category, along with the sticky term emerging, was intended to help new dancers.

I know dancers who have been performing and creating exciting work for years and are still considered emerging, whereas if they were visual art stars they’d be having a retrospective.

These terms have become the shackles of the new generation who can never make the leap to professionals, languishing in the poverty of Canadian dance funding.

Dance is hard, punishing work. The position of authority and desperation in the choreographer-dancer relationship makes this whole free labour thing smack of exploitation.

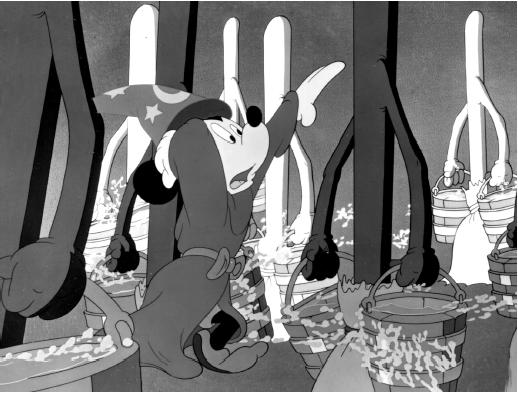

(From Disney’s Fantasia)

Comments

Agreed. This situation is both frustrating and unfair. I have a friend who jokingly refers to herself as a “full-time apprentice”…while making ends meet by waiting tables. I know so many artists who have been apprenticing for various companies since they entered the professional dance world a few years ago, and while each apprenticeship has been rewarding in its own right, these positions haven’t led to paying gigs, as we were all told would happen. Eventually.

Most dancers love their art form so much that they are willing to do it for free, especially if they think that taking on unpaid work will eventually lead to a paying gig with the company. They do it for the experience, for the exposure, and for the networking connections. In school, we were all told that apprenticing was the way to go if you wanted to get yourself known in the community, and that it was the best way to go about landing professional work – eventually. I think that these days, the humble apprentice has become somewhat stuck in limbo.

Funding for dance is slim pickings, as always. And there are many choreographers out there who have minuscule project budgets, and want to work with more than two or three bodies, but can’t afford to pay them all. The solution, more often than not, is to take on a few apprentices, pay them poorly or not at all, and graciously allow them to perform in the work (something that we apprentice dancers are always excited about). Voila, you have a larger cast for the same amount of $$. This happens in smaller companies everywhere, but it also takes place in larger companies who you’d expect would have the funding to pay their apprentices. But – precedent has been set again and again. There’s no easy solution, as choreographers will almost always be able to find someone somewhere who’s willing to dance for free.

i’m of two minds about the “eternal apprentice” (btw, that’s an excellent term; let’s see if we can spread the word around) and that other contentious moniker, “emerging artist”. melanie, i think the phenomenon of the eternal apprentice is most certainly linked to another relatively recent development in canadian society, the training wage, which is a way to squeeze more work for less money by employers because of the pressures of the market. by creating a class which you could call “the emerging retail worker”, the retail industry had been able to justify what the established dance community has done in a similar fashion. both are only responding to the pressures exerted on them by binding agreements on what is an acceptable wage, and by the actual available amount of money.

the eternal apprentice (it’s a GREAT term… i feel like you should write something substantial, with a historical perspective that we can send around to everyone in the arts community, and you should really take ownership of the word, because i think it has that je ne se quoi that makes it catchy and memorable and meaningful, and possibly a start of something big… i think you should reserve the domain name eternalapprentice.org before someone else does! 🙂 …

anyway, the eternal apprentice sounds to me like a potential for a lot of research. it connotes not only the simultaneous commodification and marginalization of young talent, but also a need and genuine desire to accommodate it nevertheless, given the limited resources.

Oh, I forgot. I did say I was of two minds about this. One could ask the question, “If I am an eternal apprentice, what is it that I could be doing better?” Perhaps the continued push for an egalitarian society (which I think is good, overall) also fosters an sense of entitlement in young professionals and artists… an unhealthy sense, I think, particularly when they don’t have enough skill or experience to execute the kind of work desired by the choreographer they have chosen to work with.

In my previous post, I condemned some abstract system of artistic supply and demand as a cause of Eternal Apprenticeship. However, I also think that if more dancers adopted the kind of exacting, self-directed rigour that Megan Walker-Straight (sorry for those who don’t know her!) embodies/embodied in her training and performance, where pretty much nothing else mattered other than her craft, I think we might actually see less eternal apprentices. Perhaps eternal apprentices are merely reaping the fruits of their enormous, but unfortunately still insufficient, labours.

How hard are we willing to work for dance? How much does it mean to us? What are we willing to sacrifice? How much more are we willing to work for and sacrifice?